Divan E Shams E Tabrizi Pdf Files

Nov 17, 2015. Dear Internet Archive Supporter. I ask only once a year: please help the Internet Archive today. We're an independent, non-profit website that the entire world depends on. Most can't afford to donate, but we hope you can. The average donation is about $41. If everyone chips in $5, we can keep this going. Aug 26, 2017. Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi In Urdu Pdf Download 480e92b22f. Lola Levine Meets Jelly and Bean new english file book download pdf. Tags: book french, audio book, book text format, You search pdf online pdf, book OneDrive, book iCloud, buy amazon bookstore download epub,.

'Divan-e Shams is a masterpiece of wisdom and eloquence. It is often said that Rumi had attained the level of a 'Perfect Master' and as such, he often dwelled in the spiritual realms that were rarely visited by others of this world. Rumi had attained spiritual heights that were attained by only a few before him or since.While the origins of Rumi’s poetry are distinctly Muslim and Sufi in nature, this hasn't stopped his poetry from being vastly widespread and influential. From German romanticism to American transcendentalism, Rumi’s influence has been broad and deep. The French writer, Maurice Barres had once confessed: ' When I experienced Rumi's poetry, which is vibrant with the tone of ecstasy and with melody, I realized the deficiencies of Shakespeare, Goethe and Victor Hugo.

' The eminent British-born Orientalist and Rumi translator, A. Arberry had once stated: ' In Rumi we encounter one of the world’s greatest poets. In profundity of thought, inventiveness of image, and triumphant mastery of language, Rumi stands out as the supreme genius of Islamic Mysticism.' The greatest Rumi scholar and translator, R. Nicholson, who was the first British-born Orientalist to translate the entire Masnavi into English, characterized Rumi and his works as: ' T he Masnavi is a majestic river, calm and deep, meandering through many a rich and varied landscape to the immeasurable ocean; the Divan is a foaming torrent that leaps and plunges in the ethereal solitude of the hills. Rumi is the greatest mystic poet of any age.'

Sir William Jones, an 18th century British scholar of the Persian language, had proclaimed that: ' I know of no writer to whom Rumi can justly be compared, except Chaucer or Shakespeare. So extraordinary a book as the Masnavi was never, perhaps, composed by Man. It abounds with beauties, and blemishes, equally great; with gross obscenity, and pure ethics; with exquisite strains of poetry, and flat puerility; with wit, and pleasantry, mixed jests; with ridicule on all established religions, and a vein of sublime piety. Rumi's Masnavi reflects a much more ecumenical spirit and a far broader and deeper religious sensibility than Dante's Divine Comedy.' 'The name Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi stands for love and ecstatic flight into the infinite. Rumi is one of the greatest spiritual masters and poetical geniuses of mankind and was the founder of the Mevlevi Sufi Order, a leading mystical brotherhood of Islam. Rumi was born in Balkh [a historic city in northern modern Afghanistan near Mazar-e Sharif, back then the eastern frontiers of the great Persian Empire], in 30 September 1207 to a family of learned theologians.

Escaping the Mongol invasion and destruction, Rumi and his family traveled extensively in the Muslim lands, performed pilgrimage to Mecca and finally settled in Konya, Anatolia, then part of Seljuk Empire. When his father Bahauddin Walad passed away, Rumi succeeded his father in 1231 as professor in religious sciences. Rumi 24 years old, was an already accomplished scholar in religious and positive sciences. If there is any general idea underlying Rumi's poetry, it is the absolute love of God. The Mevlevi rites, Sema [Sufi Dance of Whirling Dervishes] symbolize the divine love and mystical ecstasy; they aim at union with the Divine. The music and the dance are designed to induce a meditative state on the love of God.

Mevlevi music contains some of the most core elements of Eastern classical music and it serves mainly as accompaniment for poems of Rumi and other Sufi poets. The dervishes turn timelessly and effortlessly. They whirl, turning round on their own axis and moving also in orbit. The right hand is turned up towards heaven to receive God's overflowing mercy which passes through the heart and is transmitted to earth with the down-turned left hand.

While one foot remains firmly on the ground, the other crosses it and propels the dancer round. The rising and falling of the right foot is kept constant by the inner rhythmic repetition of the name of 'Allah-Al-lah, Al-lah.' ' Rumi’s teaching of peace and tolerance has appealed to men and women of all sects and creeds, and continues to draw followers from all parts of the Muslim and non-Muslim world.

As both a teacher and a mystic, his doctrine advocates tolerance, reasoning, goodness, charity and awareness through love, looking with the same eye on Muslims, Jews, Christians and others alike. Today, this message of love, peace and friendship finds strong resonation in people’s hearts.Jelaleddin Rumi was one of the great spiritual masters and poetic geniuses of mankind, and the Mevlevi Sufi order was founded to follow his teachings. The main theme and message of Rumi's thoughts and teachings is the love of God and His creatures. The focus of his philosophy is humanity and his objective is to achieve and to help others reach the state of perfect human being. Rumi founded the Mevlevi Sufi mystic order, commonly known as the 'Whirling Dervishes' and created the Sema rite, a ritualistic sacred dance to symbolically seek the divine truth and maturity. Rumi's message and teachings continue to inspire people from all religions and cultures today and show us how to live together in peace and harmony. The world of Rumi is not exclusive, but is rather the highest state of a human being - namely, a fully evolved human.

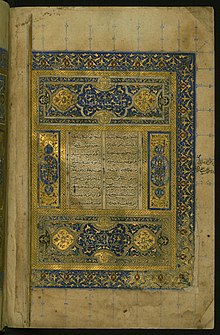

He offends no one and includes everyone, as a perfect human being who is in search of love, truth and the unity of the human soul. Rumi's very broad appeal, highly advanced thinking, humanism and open heart and mind may derive from his genuinely cosmopolitan character, as during his lifetime he enjoyed exceptionally good relations with people of diverse social, cultural and religious backgrounds. Rumi was familiar with the core message of all of them and therefore was appreciated by believers of many religions. Divan-e Shams Tabrizi or Divan-e Kabir - دیوان شمس تبریزی یا دیوان کبیر - Rumi's Great Collection of Lyrical Love Poems Dedicated to His Mystical Lover and Sufi Master, Shams of Tabriz 'Rumi's second best known work is the Divan-e Shams Tabrizi or Divan-e Kabir, totaling some 35000 couplets, which is a collection of poems describing the mystical states and expounding various points of Sufi doctrine.

While the Masnavi tends towards a didactic approach, the Divan is rather a collection of ecstatic utterances. It is well known that most of the ghazals/odes of the Divan were composed spontaneously by Rumi during the Sema or 'Mystical dance.' This dance, which later came to be known as the 'Dance of the W hirling Dervishes,' is an auxiliary means of spiritual concentration employed by the Mevlevi Sufi Order, a means which, it is said, was originated by Rumi himself. Besides approximately 35000 Persian couplets and 2000 Persian quatrains, the Divan contains 90 ghazals/odes and 19 quatrains in Arabic, a couple of dozen or so couplets in Turkish (mainly macaronic poems of mixed Persian and Turkish) and 14 couplets in Greek (all of them in three macaronic poems of Greek-Persian). The Divan is the inspiration of Rumi’s middle-aged years.

It began with his meeting Shams of Tabriz, becoming his disciple and spiritual friend, the stress of Shams’ first disappearance, and the crisis of Shams’ final disappearance. It is believed that Rumi continued to compose poems for the Divan long after this final crisis– during the composition of the Masnavi.

The Divan is filled with ecstatic verses in which Rumi expresses his mystical love for Shams as a symbol of his love for God. Shams of Tabriz was the man who transformed Rumi from a learned religious teacher into a devotee of music, dance, poetry, and founder of the Whirling Dervishes. Shams stayed with Rumi for less than two years when upset by the hostility of Rumi's disciples, spearheaded by Rumi's own son, Alauddin, one day Shams left unannounced. After the final disappearance of Sham of Tabriz, Rumi was consumed by an extended period of soul-searching. He continued to compose poems and odes to assuage his wounded heart, and this ever-growing body of work formed the basis of his book, Divan, which he dedicated to the memory of Sham of Tabriz.

These beautiful and emotional poems spoke of a platonic form of love between a student and his lost master. Rumi roamed the city at nights and danced spontaneously around uttering verses in ecstasy and lamenting the separation from his master, while his students recording the muse. This valuable wealth of mystic poetry, over 50,000 verses, are preserved in the form of what is known as Divan-e Shams Tabrizi --Rumi uses Shams as nom de plume in the poems as a glowing tribute to his mystical lover and Sufi master, Shams of Tabriz. In the ghazal/ode 1720 from his Divan-e Shams, Rumi writes: We come spinning out of nothingness, Scattering stars like the dust. The stars form a circle, And in the center we dance. Shams of Tabriz, This love of yours thirsts for my blood.

I head straight to it, Blade and shroud in hand! Fihi Ma Fihi - فیه ما فیه - Discourses of Rumi 'It contains a collection of 71 talks and lectures given by Rumi at various occasions - some formal and others informal - to his disciples. Fihi Ma Fihi is a record of those 71 spiritual discussions that often followed music and dance, the reciting of sacred poems and phrases, and the now famous Whirling Dance of Sufi Dervishes that Rumi originated to bring spiritual awakening to the masses. Like Masnavi, it was written during the last few years of Rumi’s life. Fihi Ma Fihi or The Discourses was compiled from the notes of his various disciples, so Rumi did not author the work directly. An English translation from the Persian was first published by A.J.

Arberry as Discourses of Rumi (1972), and a translation of the second book by Wheeler Thackston as Sign of the Unseen (1994). In the preface to Arberry’s translation of “Fihi Ma Fihi”, Doug Marman writes: ‘It’ refers to God. Therefore God is what God is. This is the same as the Muslim saying, ‘There is no god but GOD.’ In other words, Rumi asks, ‘What more is there to say?’ All the words here, all the stories and explanations are saying nothing more than this.

There is no more to reality than reality. It is what it is. Explanations cannot explain it. Words cannot reveal it. “Fihi Ma Fihi” refers to the “Immanent” aspect of the Cosmic Consciousness. Immanence, derived from the Latin in manere – “to remain within” – refers to the divine essence permeating the whole Cosmos and forming the basis of existence and life. Without this essence there is no existence and there is no life.

The life giving essence is at the core of each entity from elementary particles to the entire Cosmos and from viruses to human beings. This essence is also known as the Soul.

Unit Souls and the Cosmic Soul seem different but they are reflections of that nameless indescribable ocean of love and bliss. Rumi experiences this infinite ocean, he is unable to explain it and unable to describe it. He simply says “It is what It IS.”. Majalis-e Saba - مجالس سبعه - Seven Sermons of Rumi 'It contains a collection of Seven Rumi Sermons or Lectures given in seven different assemblies. The Sermons themselves give a commentary on the deeper meaning of Quran and Hadith. The Sermons also include quotations from poems of Sanai, Attar, and other Persian Sufi poets, including Rumi himself.

As his hagiographer, Aflakī relates, after Shams Tabrizi, Rumi gave sermons at the request of notables, especially his second deputy, Salah al-Din Zarkub. Throughout his life, Rumi gave many sermons in the mosques of Konya and many addresses and speeches to gatherings of his students, followers, and others. On seven of these more auspicious occasions, either Rumi’s son, Sultan Walad, or his last deputy, Husamuddin Chelebi, recorded what the Master said. These seven recorded sermons, together, are known as the Majalis-i Saba’, which translates as the Seven Sermons. Each of these seven speeches centers upon an important saying, or hadith, of Prophet Muhammad and is expounded upon with a wide variety of anecdotes, examples, and persuasive arguments.

In tone, these speeches are more businesslike and less like the poetry that characterizes Rumi’s other works. Here is a brief summary of the contents of each of the Seven Sermons of Rumi. They appear as well-organized speeches in all respects: Sermon 1: Believers should follow the example and way of Prophet Muhammad. Untold rewards will accrue to the benefit of those who adhere to the Prophet’s way in uncertain times. Sermon 2: Whoever preserves himself/herself from falling into sinful ways and who avoids arrogance, one of the worst sins, will gain spiritual richness from God. Real wealth is a contented heart.

Followers of the Truth avoid greed, arrogance, and revenge, and they advance their knowledge through education. Sermon 3: Pure and sincere faith will propel a person toward honest worship of God. Prayers should be performed in a humble frame of mind, and God’s help should be sought in all affairs. Sermon 4: God loves those who are pure at heart. God favors those who are humble and who love Him rather than the material world.

God loves those who repent to Him if they ever commit a sin. God accepts the repentance of the sincere and erases their sins. Sermon 5: The only way a person can be saved from the pitfalls of the world is through religious knowledge. Those who know nothing of religion are like an empty scarecrow.

Those who acquire religious knowledge are like doctors who heal others. Knowledge is the weapon a believer uses against sin. Sermon 6: The world is like a trap that captures any who cling too closely to it. Those who focus themselves only upon the world of the present pass through life unaware of the bigger picture. They are heedless and do not perform the tasks that God would have them do. They can only expect destruction in the next life. Sermon 7: The only way a person can understand his/her soul and how his/her motivations work is through knowledge and reason.

When a person uses his/her mind to delve deeply within self, he/she can finally begin the journey towards becoming a true lover of God.' Maktubat - مکتوبات - Letters of Rumi 'It contains a collection of 150 of Rumi's Persian Letters to his family members, friends, and men of state and of influence. The Letters testify that Rumi kept very busy helping family members and administering a community of disciples that had grown up around them. Islamic civilization was a society that placed a high value on preserving written records. In Rumi’s time, it had already been a well-established practice to collect the letters of scholars together and publish them in book form. Thus, Rumi’s students saved many of his letters and collated about 150 of them in a book. This collection of letters is called the Maktubat, or Letters. In keeping with Rumi’s religious and philosophical nature, all of these letters are liberally sprinkled with references from the Quran, the sayings of Prophet Muhammad, anecdotes, quotes from famous writers, and poems.

Rumi’s Letters, which were written to rulers, friends, students, and others, fall into three basic categories that can be summarized as follows. Sir William Jones, an eighteenth-century British scholar of the Persian language, proclaimed that “I know of no writer to whom Rumi can justly be compared, except Chaucer or Shakespeare.

So extraordinary a book as the Masnavi was never, perhaps, composed by Man. It abounds with beauties, and blemishes, equally great; with gross obscenity, and pure ethics; with exquisite strains of poetry, and flat puerility; with wit, and pleasantry, mixed jests; with ridicule on all established religions, and a vein of sublime piety. The Masnavi reflects a much more ecumenical spirit and a far broader and deeper religious sensibility than Dante's Divine Comedy. Most interpreters have sought to expound the Masnavi in terms of the pantheistic system associated with Ibn al-Arabi, but this is doing grave injustice to Rumi. He is essentially a poet and a mystic, not a philosopher and logician. The nature of Rumi's experience is essentially religious.

By religious experience is not meant an experience induced by the observance of a, code of taboos and laws, but an experience which owes its being to love; and by love Rumi means 'a cosmic feeling, a spirit of oneness with the Universe.' 'Love,' says Rumi, 'is the remedy of our pride and self-conceit the physician of all our infirmities. Only he whose garment is rent by love becomes entirely unselfish.' ' Rumi is perhaps the only example in world literature of a devoted prose writer who suddenly burst forth into poetry during middle age to become a truly great mystical poet for all time.

This book, a long-overdue reckoning of his life and work, begins with a description and examination of the living conditions in 13th-century Persia. Building on this context, Afzal Iqbal [the eminent 20th century India-born scholar of Rumi] proceeds to fully analyze the formative period of Rumi's life leading up to 1261--when he began the monumental work of writing the Mathnawi. Toward the end of the book, Iqbal more generally investigates Rumi's thought and includes translations of those portions of the Mathnawi that have been hitherto unavailable in English. Combining an unparalleled familiarity with the source material, a total and critical understanding of the subject, and a powerful and readable prose style, this is an extraordinary study of a truly remarkable poet and mystic.' 'Rumi entitled his collection of odes Divan-I Shams-i-Tabriz, the Mathnawi he calls Husami Namah- the Book of Husam. Shams was the hero of the Divan, Husamuddin is invoked as the inspiring genius of the Mathnawi.

Rumi took nearly twelve years to dictate 25.700 verses to Husamuddin. The modern reader demands a summary which he can dispose of in an hour. This is not possible. Even the best of summaries would do serious damage to the work. We could only attempt an outline, often using the words and employing the idiom of the author.Rumi is aware of the massive contribution he is making.

In the prose introduction of Book IV, without being unduly immodest he says, 'it is the grandest of gifts and the most precious of prizes;... It is a light to our friends and a treasure for our (spiritual) descendants.' He is now a poet with a purpose. He asks, Does any painter paint a beautiful picture for the sake of the picture itself? Does any potter make a pot in haste for the sake of the pot itself and not in hope of the water? Does any bowl-maker make a finished ~owl for the sake of the bowl itself and not for the sake of the food? Does any calligrapher write artistically for the sake of writing itself and not for the sake of the reading?

In the last volume of the Mathnawi, referring to his critics, Rumi complains that the 'sour people are making us distressed, but what is to be done? The message must be delivered. 'Does a caravan ever turn back from a journey on account of the noise and clamour of the dogs?, ‘If you are thirsting for the spiritual Ocean,' says Rumi, 'make a breach in the island of the Mathnawi. Make such a great breach that at every moment you will see the Mathnawi to be only spiritual.

‘I saw my Lord; I do not worship a Lord whom I have not seen!’ Rumi says: So long as you are under the dominion of your senses and discursive reason, it makes no difference whether you regard God as transcendent or immanent, since you cannot possibly attain to true knowledge of either aspect of His nature. The appearance of plurality arises from the animal soul, the vehicle of sense-perception. The 'human spirit' is the spirit which God breathed into Adam, and that is the spirit of the Perfect Man.

Essentially it is single and indivisible, hence the Prophets and saints, having been entirely purged of sensual affections, are one in spirit, though they may be distinguished from each other by particular characteristics. 'The world of creation is endowed with (diverse) quarters and directions, (but) know that the world of the (Divine) Command and Attributes is without (beyond) direction.... No created being is unconnected with Him: the connection... Is indescribable, 'because in the spirit there is no separating and uniting, while (our) thought cannot think except [in terms] of separating and uniting. Intellect is unable completely to comprehend this reality for it is in bondage to its own limitation of thinking in categories it has coined for itself.

That is why the Prophet enjoined: 'Do not seek to investigate the Essence of God.' In the Proem of Book V of Masnavi, Rumi says to God: Thy dignity hath transcended intellectual apprehension: in describing thee the intellect has become an idle fool. (Yet), although this intellect is too weak to declare (what thou art), one must weakly make a movement (attempt) in that (direction). Know that when the whole of a thing is unattainable the whole of it is not (therefore to be) relinquished. If you cannot drink (all) the flood-rain of the clouds, (yet) how can you give up water-drinking?

If thou wilt not communicate the mystery, (at least) refresh (our) apprehensions with the, husk thereof. The man who has seen the vision is alone unique and original; and he cannot give expression to his vision for there are nor words to describe the experience which is impossible to communicate. When the Prophet left Gabriel behind and ascended the highest summit open to man the Qur’an only says that ‘Then He revealed to His servant that which He revealed.’ What he saw is not explained; it cannot be explained and it cannot be described. A stage arrives when silence becomes the height of eloquence!

And yet we cannot remain content with knowledge borrowed from others. We must strive to experience for ourselves that unique indescribable vision. Our bane is that we see with borrowed light and color and we think it is our own. Rumi asks God ‘what fault did that orchard commit, that it has been stripped of the beautiful robes and has been plunged into the dreary destruction of autumn?' The reply comes: ‘The crime is that he put on a borrowed adornment and pretended that these robes were his own property. We take them back, in order that he may know for sure that the stack is Ours and the fair ones are (only) gleaners; That he may know that those robes were a loan: ‘twas a ray from the Sun of Being....

Thou art content with knowledge learned (from others): thou hast lit thine eye at another lamp. He takes away his lamp, that thou mayst know thou art a borrower, not a giver.’. 'This work attempts to present Rumi to the English-speaking world and to shed light on his life as seen from within the Islamic mystical tradition.

The knowledge presented in this work comes from Sefik Can, a great expert of Rumi and who used to be the highest authority, Sertariq, of the Mevlevi Sufi order in Turkey until he passed away on January 24, 2005. According to Rumi, beauty takes us from ourselves, frees us from the prison of the body, and brings us closer to another realm, to God. Thus we find God within the impact of the fine arts on sensitive people.' ' The Mawlawiyah Order - طریقه مولویه (known as Mevlevi, or Mevleviye in Turkey) - one of the most well-known of the Sufi Orders - was founded in 1273 by Rumi's followers after his death, particularly his last deputy, Husamuddin Chelebi, and his son and successor, Sultan Walad in Konya, central Turkey from where they gradually spread throughout the Ottoman Empire. Today, the Mawlawīyah or Mevlevi Sufi Order can be found in many Turkish communities throughout the world, but the most active and famous places for their activity are still Konya and Istanbul in Turkey. The first successor in the leadership of Mevlevi Sufi Order was Rumi's last deputy, Husamuddin Chalabi, after whose death in 1284 Rumi's younger and only surviving son, Sultan Walad (died 1312), was installed as grand master of the Sufi Order. The leadership of the Order has been kept within Rumi's family in Konya uninterruptedly since then.

The Mevlevi Sufis, also known as Whirling Dervishes of Rumi, believe in performing their Zikr (Remembrance of God) in the form of Sema Sufi Whirling Dance. Dervish is a common term for an initiate of the Sufi path; the whirling is part of the formal Sema ceremony and the participants are properly known as Semazen or Whirlers. Rumi developed a form of combined mobile meditation, symbolism, and teaching which became the basis of the Mevlevi Dervishes, popularly called the Whirling Dervishes and also the Mawlawi Dervishes in the Muslim world. The participants enact the turning of the planets around the sun, a symbol of man linked to the center which is God, source of life, but it is also an internalized turning of the body toward the soul, likewise source of life. Rumi tried to map out a system in which sound, motion and one-pointed concentration of thought would lead to an end to the personal self and union with the Higher Self. During the time of Rumi (as attested in the Manaqib ul-Arefīn by Rumi's hagiographer, Aflakī), his followers used to gather for musical and 'turning' practices.

Rumi himself was a notable musician who played the robab (stringed-lute), although his favorite instrument was the ney or reed flute. The music accompanying the Sema ceremony consists of settings of poems from the Rumi's Masnavi and Divan, or of Rumi's son and successor, Sultan Walad's poems. The Mawlawiyah was a well-established Sufi Order in the Ottoman Empire, and many of the members of the Order served in various official positions of the Caliphate. The center for the Mawlawiyyah was in Konya, central Turkey. There is also a Mevlevi monastery in Istanbul near the Galata Tower in which the Sema ceremony is performed and accessible to people of all faiths and backgrounds.' Do you know what Sema, the Sufi Dance of Whirling Dervishes is? Sema is letting go completely of your existence and tasting eternity in non-existence.

Sema is hearing the affirmation sound of separating from Self, and reaching God. Sema is seeing and knowing Lord, our Friend; and hearing, through the Divine Veils, the Secrets of God. Sema is struggling hard with your carnal soul, your own ego, and throwing it to the ground like a half-slain beast. Sema is opening the heart like Shams of Tabriz, and clearly seeing the Divine Light within. ~Rumi The Mevlevi Religious Sema Ceremony - Whirling Dervishes • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •.

'We live in a world of illusion bound by fear. To awaken the soul is to enlighten the mind. There is one eternal, simple truth: I AM. And because that is so, everything is because I AM. I AM God the Creator, everything else I am not, although I can be if I so choose. To illuminate the mind is to confront fear, to confront fear is to examine our limitations and boundaries.

To open the mind is to invite the courageous soul into those places where once resided fear and worry. As the soul awakens from the slumber induced by being human, we are created, re-created anew.I AM is the spark of a God, all knowing, omnipotent, omnipresent, eternal and invincible.

I AM always with God, in God, as God, of God.' ~Shams Tabrizi. 'Shams Tabrizi (1184-1247) was a mysterious Persian mystic, credited as the spiritual master of Rumi, and is referenced with great reverence in Rumi’s poetic collection, in particular Divan-e Shams Tabrizi (The Works of Shams of Tabriz). A wandering Sufi mystic born in Tabriz, Iran, Shams became Rumi’s beloved companion in Konya, Turkey.

Rumi had been a sober Muslim scholar, teaching Islamic Law and Theology to a small circle of students, but the coming of Shams turned him into a devotee of music, dance, and poetry. After Shams' final disappearance, Rumi attributed more and more of his own poetry to Shams as a sign of love for his departed friend and master. In Rumi's poetry, Shams becomes a symbol of God's Love for mankind; Shams was a sun ('Shams' means 'Sun' in Arabic) shining the Light of God on Rumi.'

' Maqalat-e Shams-e Tabrizi (Discourse of Shams Tabrizi) is a Persian prose book written by Shams of Tabriz [Rumi's Spiritual Master]. The Maqalat seems to have been written during the later years of Shams, as he speaks of himself as an old man. Overall, it bears a mystical interpretation of Islam and contains spiritual advice. Maqalat-e Shams-e Tabrizi is one of the two or three most important prose texts providing us with context for the ideas expressed in the Masnavi and Divan of Jalaluddin Rumi. The following excerpts from the Maqalat provide us some insight into the profound Sufi thoughts of Shams of Tabriz: Blessing is excess, so to speak, an excess of everything. Don't be content with being a faqih (religious scholar), say I want more – more than being a Sufi (a mystic), more than being a mystic – more than each thing that comes before you.

Man has two qualities: One is (his) need. Through this quality, he hopes and he has his eyes on reaching the goal. The other quality is being without a need.

What hope can you have from being without need? What is the utmost end of a need? Finding what has no needs! What is the ultimate end of seeking? Finding what is sought. What is the ultimate end of the sought?

Finding the seeker! Find a true seeker.' 'Rumi’s Sun collects many lessons and discourses from Shams of Tabriz, the Sufi mystic and spiritual master who was the catalyst for Rumi’s awakening. His teachings and insights inspired much of Rumi’s poetry and are still celebrated today by all Sufi. Translated by two noted students of Sufi [ Camille Helminski and Refik Algan], Shams’ timeless teachings are presented here in their traditional order.

Through the book, readers discover the teachings that made Rumi dance and gain access into Sufi traditions and the power of mystical love. 'The Sun had a special significance for Rumi because it alluded to his master, Shams—the one who awakened the truth within Rumi.

Rumi’s use of the terms “Shams,” “Shams-e Tabriz” (Shams of Tabriz), and “Shamsuddin” refers not only to his master but also to the many aspects of the Beloved, embodied in Shams: “Shams” symbolizes the power of grace, the power that awakens the truth within us; “Shams” symbolizes the inner sunrise, the inner light of consciousness, one’s own soul and its awakening. There are several accounts of this historic meeting. One version says that during a lecture of Rumi's, Shams came in and dumped all of Rumi's books--One handwritten by his own father-into a pool of water. Rumi thought the books were destroyed, but Shams retrieved them, volume by volume, intact. Another version says that at a wave of Shams' hand, Rumi's books were engulfed in flames and burned to ashes.

Shams then put his hand in the ashes and pulled out the books. (A story much like the first.) A third account says that Rumi was riding on a mule through a square in the center of Konya. A crowd of eager students walked by his feet. Suddenly a strange figure dressed in black fur approached Rumi, grabbed hold of his mule's bridle, and said: 'O scholar of infinite knowledge, who was greater, Muhammad or Bayazid of Bestam?' This seemed like an absurd question since, in all of Islam, Muhammad was held supreme among all the prophets.

Rumi replied, 'How can you ask such a question?-No one can compare with Muhammad.' 'O then,' Shams asked, 'why did Muhammad say, 'We have not known Thee, O God, as thou should be known,' whereas Bayazid said, 'Glory unto me! I know the full glory of God'?' With this one simple question--and with the piercing gaze of Shams' eyes-Rumi's entire view of reality changed.

The question was merely an excuse. Shams' imparting of an inner awakening is what shattered Rumi's world.

The truths and assumptions upon which Rumi based his whole life crumbled. This same story is told symbolically in the first two accounts, whereby Rumi's books-representing all his acquired intellectual knowledge, including the knowledge given to him by his father-are destroyed, and then miraculously retrieved or 'resurrected' by Shams. The books coming from the ashes, created anew by Shams, represent the replacing of Rumi's book-learned knowledge (and his lofty regard for such knowledge) with divine knowledge and the direct experience of God. Rumi was totally lost in this newfound love that his master revealed, and all his great attainments were blossoming through that love. Every day was a miracle, a new birth for Rumi's soul. He had found the Beloved, he had finally been shown the glory of his own soul. Then, suddenly, eighteen months after Shams entered Rumi's life, he was gone.

He returned some time later, for brief period, and then he was gone again forever. Some accounts say that Shams left in the middle of the night and that Rumi wandered in search of him for two years.

(Perhaps a symbolic and romantic portrayal of the lover in search of his missing Beloved.) Other accounts report that Shams was murdered by Rumi's jealous disciples (symbolizing how one's desires and lower tendencies can destroy the thing held most dear). Without Shams, Rumi found himself in a state of utter and incurable despair; and his whole life thereafter became one of longing and divine remembrance.

Rumi's emptiness was that of a person who has just lost a husband or a wife, or a dear friend. Rumi's story shows us that the longing and emptiness we feel for a lost loved one is only a reflection, a hologram, of the longing we feel for God; it is the longing we feel to become whole again, the longing to return to the root from which we were cut. (Rumi uses the metaphor of a reed cut from a reed bed and then made into a flute-which becomes a symbol of a human separated from its source, the Beloved. And as the reed flute wails all day, telling about its separation from the reed bed, so Rumi wails all day telling about being separated from his Beloved.).

I first came to Maulana with the understanding that I would not be his Shaykh (Sufi Master). God has not yet brought into being on this earth one who could be Maulana's Shaykh; he would not be a mortal.

But nor am I one to be a disciple. It's no longer in me. Now I come for friendship, relief. It must be such that I do not need to dissimulate. Most of the prophets have dissimulated. Dissimulation is expressing something contrary to what is in your heart. In my presence, as he listens to me, Maulana considers himself - I am ashamed to even say it - like a two-year-old child or like a new convert to Islam who knows nothing about it.

Amazing submissiveness! Regarding me and Maulana, the intended aim of the world's existence is the encounter of two friends of God, when they face each other only for the sake of God, far distant from lust and craving.

The purpose is not for bread, soup with bread crumbs, butcher, or the butcher's business. It is such a moment as this, when I am tranquil in the presence of Maulana. Beyond these outward spiritual leaders who are famous among the people and mentioned from the pulpits and in assemblies, there are the hidden saints, more complete than the famous ones. And beyond them, there is the sought one that some of the hidden saints find. Maulana thinks that I am he, but that's not how I see it.

The story of the sought one cannot be found in any book, nor in the explanations of religion, nor in the sacred treatises - all those are explanations for the path of the seeker. We've only heard about the sought ones - nothing more has been said. In the whole world, words belong only to the seeker. The sought one has no mark in this world. Every mark is the mark of the seeker.

These arrows will take you to the world of the Real. They are in the quiver there, but I can't shoot them. The arrows I shoot all go back into the quiver from where they come. There may be one fault in a man that conceals a thousand qualities, or one excellence that conceals a thousand faults. The little indicates much.

Being the companion of the folk of this world is fire. There must be an Abraham if the fire is not going to burn. I have no business with the common folk of the world; I have not come for their sake. Those people who are guides for the world unto God, I put my finger on their pulses.' While many other poets have a mystical vision and then try to express it in a graspable language, Rumi has never attempted to bring his visions to the level of the mundane. He has always expected, nay, demanded the reader to reach higher and higher in his or her own spiritual understanding, and then perhaps be able to appreciate what Rumi was saying. Perhaps this is why there are many layers to his poetry not so much because of his writing, but because of our understanding.

As we transcend in our understanding, we grasp more and more of what he conveyed to us. ' What have I to do with poetry?

By Allah, I care nothing for poetry, and there is nothing worse in my eyes than that. It has become incumbent upon me, as when a man plunges his hands into tripe and washes it out for the sake of a guest's appetite, because the guest's appetite is for tripe. I have studied many sciences and taken much pain, so that I may be able to offer fine and rare and precious things to the scholars and researchers, the clever ones and the deep thinkers who come to me. God most High Himself willed this. He gathered here all those sciences, and assembled here all those pains, so that I might be occupied with this work. What can I do? In my own country and among my own people there is no occupation more shameful than poetry.

If I had remained in my own country, I would have lived in harmony with their temperament and would have practiced what they desired, such as lecturing and composing books, preaching and admonishing, observing abstinence and doing all the outward acts.' 'This spirituality that Rumi represents has obviously touched a very deep nerve in the American psyche. ' 'Rumi, the 13th century [Afghan-born] Muslim mystic, is now America’s bestselling poet. Amazon lists more than a hundred books of his poetry, and Hollywood stars like Madonna and Martin Sheen have made a CD of his writings.

In a country where Pulitzer Prize-winning poets often struggle to sell 10,000 books, Coleman Barks' translations of Rumi have sold more than a quarter of a million copies. Recordings of Rumi poems have made it to Billboard's Top 20 list. And a pantheon of Hollywood stars have recorded a collection of Rumi's love poems - these translated by holistic-health guru Deepak Chopra.Put it all together and you've got a Rumi revival that's made the 13th-century Persian wordsmith the top-selling poet in America today. In America, Rumi is a teacher of universal spiritual love that crosses religions. Rumi was truly focused on the inner experience, and his writings about the spiritual journey have resonated with people from all walks of life. Rumi is also able to 'evoke ecstasy from the plan facts of nature and everyday life' - and in our fast-paced world, that's something we can all appreciate. ' Excerpts from 'An Americanized Rumi who speaks to the hearts of hundreds of thousands of people and builds bridges of understanding between the Muslim World and the West is, after all, better than an Academized Rumi who speaks to no one.'

'.The Western world has for decades been culling through the most alluring and exotic blooms of Eastern poetry and philosophy in search of a 'spirituality' completely unencumbered by the spiky thorns of 'religion.' “When His Highness sends a ship to Egypt, do you suppose he worries whether the ship’s mice are comfortable or not.” The dervish answered. This dervish was Jalaluddin Mohammad Rumi, also known as Mavlana-i-Balkhi, the greatest metaphysical thinker and Sufi poet of all times.As the labyrinth of suffering and injustice and fever of war is raging in our world today, the West looks upon the East for inspiration as Voltaire did in his turbulent age. For our age, Rumi’s poetry offers the remedy for the apocalyptic hysteresis of our time. It is the prime reason why Rumi is becoming increasingly popular in the West. The medieval poet is loved and read in the West and he still is a bestseller in the US. His ideas and poetic legacy still haunt universities, pubs, spiritual industries, valentine day, theater, opera, ballet, film etc.

Rumi and Idris Shah himself were among the great inspirers for the Western esotericism, New Age in the 1960s. Rumi’s spiritual doctrine of God as an apex of a pyramid with numerous paths leading to it was adapted by the New Agers. This led within the movement the notion of unity and harmony between all religions of the world. With the help of a spiritual master, one can get access to such a high consciousness and a cosmic energy beyond human physical faculties. Morgan Heritage Mission In Progress Album Download more.

The universal message of Rumi is a hopeful alternative to the ignorance and lack of spirituality in modern times. Rumi's writings of the thirteenth century advocate an understanding that there is something beyond religion and scholarly learning that can open our eyes to the reality beyond this existence; for Rumi we must climb a spiritual ladder of love. Furthermore, Rumi envisioned a universal faith, embodying all religions, because he understood that the cause of every religious conflict is ignorance. Rumi implies that religiosity consists in something other than outward religions. Real belief is apparent only on the inside of a person, which is not visible.

Therefore, Rumi makes it clear that the religion of love involves loving the eternal and invisible source of existence.' 'Rumi is thus seen, not just as an icon of Islamic civilization (or of Afghan, Iranian, Tajik or Turkish national heritage), but of global culture. And, indeed, the popular following he enjoys in North America as a symbol of ecumenical spirituality is evident in bookstores, poetry slams, church sermons and on the internet. Some claim that Rumi is the bestselling poet in the United States, achieving great commercial success at the hands of authors who 'translate' despite not speaking the original language. Since another Persian poet, Omar Khayyam (d.

1121), once had societies dedicated to him in every corner of the Anglophone world, but is relatively little read today, we may well ask whether Rumi's recent fame in the West represents just another passing fad. But might he have something profound to say about, not only the paradigm of new age thought and spirituality, but also the mystical traditions of the other established religions?' Excerpts from by one of the greatest contemporary American scholars of Rumi, Professor Franklin Lewis. Franklin Lewis' Major Works on Rumi are: MUST READ.T he Quintessential Book on Rumi 'An astounding work of scholarship by Prof. Lewis, which brings Rumi, his father, his son, Shams i Tabriz, and the entire world of medieval Konya to life in this monumental biography of Rumi and the Mevlevi Sufi Order he founded. Setting a benchmark in Rumi studies, this award-winning work examines the background, the legacy, and the continuing significance of this thirteenth-century mystic, who is today the best-selling poet in the United States. Lewis has drawn on a vast array of sources, from writings of the poet himself to the latest scholarly literature, to produce this detailed survey of Rumi's life and work.

In addition to offering fresh perspectives on the philosophical and spiritual context in which Rumi was writing, and providing in-depth analysis of his teachings, Lewis pays particular attention to why Rumi continues to enjoy such a huge following in the West. Also featured in this ground-breaking study are new translations of over fifty of Rumi's poems, and never before seen prose, together with extensive commentaries and a full annotated bibliography of works by and about Rumi.'

'It will simply not do to extract quotations out of context and present Rumi as prophet of the presumptions of an unchurched and syncretic spirituality. While Rumi does indeed demonstrate a tolerant and inclusive understanding of religion, he also, we must remember, trained as a preacher, like his father before him, and as a scholar of Islamic law. Rumi did not come to his theology of tolerance and inclusive spirituality by turning away from traditional Islam or organized religion, but through an immersion in it; his spiritual yearning stemmed from a radical desire to follow the example of the Prophet Muhammad and actualize his potential as a perfect Muslim.To understand Rumi one must obviously understand something of the beliefs and assumptions he held as a Muslim. Rumi's beliefs derived from the Koran, the Hadith, Islamic theology and the works of Sunni mystics like Sana i, Attar, and his own father, Baha al-Din Valad.' Excerpts from Prof.

Franklin Lewis' monumental work. 'Timeless and eternal, distilled from the deepest spirit, the poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi is loved the world over. In this beautifully presented volume of new translations, Franklin D. Lewis draws from the great breadth of his work, in all its varied aspects and voices. Working directly from the original Persian, Lewis brings to this translation not only the latest scholarship in Persian and English, but a deftness and lightness of touch that allows for a profound sensitivity to Rumi's mystical and philosophical background. Complete with a detailed introduction and notes, this is a perceptive, insightful, and deeply moving collection that will prove inspirational to both keen followers of Rumi's work and readers discovering the great poet for the first time.' Rumi - Ghazal/Ode # 1855 from Divan-e Shams - Translated from Farsi or Persian by the eminent American-born scholar of Rumi, Prof.

Franklin Lewis: How could I know melancholia Would make me so crazy, Make of my heart a hell Of my two eyes raging rivers? How could I know a torrent would Snatch me out of nowhere away, Toss me like a ship upon a sea of blood That waves would crack that ship’s ribs board by board, Tear with endless pitch and yaw each plank That a leviathan would read its head, Gulp down the ocean’s water, That such an endless ocean could dry up like a desert, That the sea-quenching serpent could then split that desert Could jerk me of a sudden, like Korah, with the hand of wrath, Deep into a pit?

When these transmutations came about Nod desert, not sea remained in sight How should I know how it all happened Since how is drowned in the Howless? What a multiplicity of how could I knows! But I don’t know For to counter The sea rushing in my mouth I swallowed a froth of opium. 'The Sufi Path of Love: The Spiritual Teachings of Rumi is the most accessible work in English on the greatest mystical poet of Islam, providing a survey of the basic Sufi and Islamic doctrines concerning God and the world, the role of Man in the cosmos, the need for religion, Man's ultimate becoming, the states and stations of the mystical ascent to God, and the means whereby literature employs symbols to express 'unseen' realities. William Chittick translates into English for the first time certain aspects of Rumi's work. He selects and rearranges Rumi's poetry and prose in order to leave aside unnecessary complications characteristic of other English translations and to present Rumi's ideas in an orderly fashion, yet in his own words.' Excerpts from by one of the greatest contemporary American scholars of Rumi, Prof.

Chittick ' Although Rumi has become one of America’s favorite poets, very little is known about the underlying metaphysical foundation which illuminates his language. Rumi is not a great poet in spite of Islam, He’s a great poet because of Islam. It’s because he lived his religion fully that he became this great expositor on beauty and love. Rumi has come to embody a kind of free-for-all American spirituality that has as much to do with Walt Whitman as Muhammad. Rumi’s work has become so universal that it can mean anything; readers use the poems for recreational self-discovery, finding in the lines whatever they wish. In the modern West, Jalaluddin Rumi has become the best known Persian poet. Some Persian speakers may consider him the greatest poet of their language, but not if they are asked to stress the verbal perfections of the verses rather than the meaning that the words convey.

Rumi's success in the West has to do with the fact that his message transcends the limitation of language. He has something important to say, and he says it in a way that is not completely bound up with the intricacies and beauty of the Persian language and the culture which that language conveys, nor even with poetry (he is also the author of prose works, including his Discourses, available in a good English translation by A.J. One does not have to appreciate poetry to realize that Rumi is one of the greatest spiritual teachers who ever lived. Rumi's greatness has to do with the fact that he brings out what he calls 'the roots of the roots of the roots of the religion,' or the most essential message of Islam, which is the most essential message of traditional religion everywhere: Human beings were born for unlimited freedom and infinite bliss, and their birthright is within their grasp. But in order to reach it, they must surrender to love.

What makes Rumi's expression of this message different from other expressions is his extraordinary directness and uncanny ability to employ images drawn from everyday life. Beauty, Rumi knows, is a profound need of the human soul, because God is beautiful and the source of all beauty, and God is the soul's only real need.For Rumi, separation from Shams was the outward sign of separation from God, which is only half the story. As much as Rumi complains of separation, he celebrates the joys of union. Shams, he lets us know, never really left him, nor was Rumi ever truly separate from God. Shams Tabrizi is but a pretext- I display the beauty of God's gentleness, I!' Excerpts from by one of the greatest contemporary American scholars of Rumi, Prof. Chittick: ' Rumi is justly celebrated as one of the great poets of human history.

When I started reading him as an undergraduate 45 years ago, I did not know Persian and relied on the work of R. Nicholson, who produced the first critical edition of Rumi's 25,000-verse Mathnawi along with a complete English translation and two volumes of commentary (eight volumes in all). At that time Rumi was practically unknown outside the field of Middle East studies, so his popularity in the West is a recent phenomenon. In the Persianate world (which extends from the Balkans through Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent), he has been a cultural icon for centuries. Although he is now far better known in the West than he was 40 years ago, the understanding of what he is actually talking about seems to have decreased.

It was not easy to plow through Nicholson, but one did learn a great deal about the religious and philosophical content of Rumi's teachings. Having breezed through one of the popular selections, one comes out feeling good. Everyone recognizes that Rumi was a poet of love. This means that most people see him as an oddity in Islamic history. When we situate him in his own historical context, however, we see that he spoke for the mainstream. What made him stand out was that he got to the heart of the matter more quickly and much more enticingly than most authors.

He makes his agenda explicit in the introduction to the Mathnawi: He is explaining 'the roots of the roots of the roots of the religion,' that is, the Islamic religion founded by the Koran and Muhammad. Rumi gave a great variety of names to the human participation in God's love -- hunger, thirst, need, desire, craving, passion, fire, burning. Like many others, he identified love with the 'poverty' mentioned in the Koranic verse, 'O people, you are the poor toward God, and God is the rich, the praiseworthy' (35:15).

Love is that empty spot in our hearts that we can never fill, because it craves the infinite riches of the Hidden Treasure. Once upon a time, Rumi says, we were fish swimming in the ocean, unaware of the water and ourselves. The ocean wanted to be recognized, so it threw us up on dry land. We flip after this, we flop after that, pursuing an ever more elusive happiness.

Is the ocean tormenting us? It put us here. But, the more we burn, the more intensely we will love the ocean's beauty when it calls us back.' ' The earliest introductions of Sufism to America took place in the early 1900’s through scholars, writers, and artists who often accessed information on Sufism through the Orientalist movement. Examples of Western figures who were influenced by Sufism include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Rene Guenon, Reynold Nicholson, and Samuel Lewis.

These individuals helped to introduce concepts of Sufism to larger audiences through their writings, discussions and other methods of influence. Emerson, for example, was influenced by Persian Sufi poetry such as that of the poet Saadi, and this influence was then reflected in Emerson’s own poetry and essays.

Rene Guenon incorporated information about Sufism into his traditionalist philosophy, and Nicholson offered Western readers some of the great Sufi works for the first time in the English language, especially the Mathnawi of Jalaluddin Rumi. The first major Sufi figure in the United States was Hazrat Inayat Khan, a musician from India. He blended aspects of Sufism and Islam with other spiritual, musical and religious concepts and practices.

He did not actually consider his group a Sufi group and preached a Universalist spiritual movement. Hazrat believed destiny had called him to speed the “Universal Message of the Time” which maintained that Sufism was not essentially tied to historical Islam, but rather consisted of timeless, universal teaching related to peace, harmony, and the essential unity of all human beings. Hazrat Inayat Khan’s Sufi Order in America, called ‘The Sufi Order in the West’ was founded in 1910.'

Excerpts from. ' The poetry of Jelal-ud-Din Rumi has made the greatest impression upon humanity. The original words of Rumi are so deep, so perfect, so touching, that when one repeats them hundreds and thousands of people are moved to tears. They cannot help penetrating the heart. This shows how much Rumi himself was moved to have been able to pour out such living words. [after meeting Shams of Tabriz], Rumi experienced a wonderful upliftment, a great joy and exaltation. In order to make this exaltation complete, Rumi began to write verses, and the singers used to sing them; and when Rumi heard these beautiful verses sung by the singers with their rabab, the Persian musical instrument, he experienced the stage known to Yogis as Samadhi, which in Persian is called Wajad..' Excerpts from.

These ideas on the nature of Mysticism inspired Karl Marx, who later gave a theory to uncover the mysticism of capital and capital accumulation in the capitalist social system. Hence, the mysticism of Rumi led to the development of Marx's theory on commodity fetishism.

Capital, Volume I was the first of the three volumes in Karl Marx's monumental work, Das Kapital. Section 4 of the first chapter, titled 'The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof,' is where Marx explained what he saw as the 'mystical' character of commodities. Marx wrote, 'A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties. For Marx, the fetishism of commodities originated in the peculiar social character of the labor that produced them.

His conception of their nature derived itself from Hegel's definition of 'mystical,' and this definition, in turn, was Hegel's reflection on Rumi's poetry. It is indeed remarkable how far reaching the influence of Rumi can be, from inspiring a new genre of poetry to theories in political-economy. 'Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, or R. Nicholson (1868 – 1945), was an eminent British Orientalist and scholar of both Islamic Literature and Islamic Mysticism, Sufism.

Nicholson is unanimously regarded as the greatest scholar and translator of Rumi in the English language. A professor for many years at the Cambridge University in England, he dedicated his life to the study of Islamic Mysticism and was able to study and translate major Sufi texts in Arabic, Farsi or Persian, and Ottoman Turkish. Nicholson's monumental achievement was his work on Rumi's Masnavi (done in eight volumes, published between 1925-1940). He produced the first critical Persian edition of Rumi's Masnavi, the first full translation of it into English, and the first commentary on the entire work in English. This work has been highly influential in the field of Rumi studies worldwide. Nicholson also produced two volumes which condensed his work on the Masnavi which were aimed at the popular level: Tales of Mystic Meaning (1931) and Rumi: Poet and Mystic (1950). In addition, Nicholson published the first information about Rumi's Discourses (Fihi-Ma-Fihi) in the English language (in a 1924 article in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society).' 'The Divani Shamsi Tabriz is a masterpiece of Persian literature and a classic work in the history of Sufiism.

With his Masnavi it is one of the key writings of the renowned Persian mystic poet Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-1273). Professor Nicholson's English translation of selected poems from the Divan of Rumi was first published in 1898, and is often credited as being the best-known version in a European language. It is suitable for scholars and students of Persian literature and for all those interested in the mystical literature of Islam. The Persian text is printed with facing English translations, and there are copious notes, a lengthy introduction, appendices and indices.' 'Jalaluddin Rumi (1207-73) was the greatest of the Persian mystical poets. In his extensive writings he explored the profound themes that had gradually evolved with the long succession of Sufi thinkers since the ninth century, such as the nature of truth, of beauty, and of our spiritual relationship with God.

Nicholson translated this inspiring collection of mystical poems shortly before his death. It contains delicately rhythmical versions of over a hundred short passages from Rumi's greatest works, together with brief yet illuminating explanatory notes. With this attractive and accessible translation, a wider readership can appreciate the range and depth of Rumi's intellect and imagination, and discover why it is so often said that in Rumi the Persian mystical genius found its supreme expression.' 'Arthur John Arberry or A. Arberry (1905-1969) was a British Orientalist, scholar, translator, editor, and author who wrote, translated, or edited about 90 books on Persian and Arab language subjects. He specialized in Sufi studies, but is also known for his excellent translation of the Koran.

Arberry attended Cambridge University, where he studied Persian and Arabic with R. Nicholson, an experience which he considered the turning point of his life. After graduation, Arberry worked in Cairo as head of the classics department at Cairo University. Arberry is also notable for introducing Rumi's works to the West through his selective translations.'

'Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–73), legendary Persian Muslim poet, theologian, and mystic, wrote poems acclaimed through the centuries for their powerful spiritual images and provocative content, which often described Rumi’s love for God in romantic or erotic terms. His vast body of work includes more than three thousand lyrics and odes. This volume includes four hundred poems selected by renowned Rumi scholar A. Arberry, who provides here one of the most comprehensive and adept English translations of this enigmatic genius. Mystical Poems is the definitive resource for anyone seeking an introduction to or an enriched understanding of one of the world’s greatest poets.' Excerpts from: 'Everyone likes a mirror, and is in love with reflections of their own attributes and attainments, but friends you misses the true nature of the face. You think this bodily veil is a face, and the mirror of this veil is the mirror of your face.

Uncover your face, so you can know for sure the mirror of your true self. The true Sufi is like a mirror where you see your own image, for “The believer is a mirror of their fellow believers.”. A mirror shows no image of itself. Any image it reflects is the image of another.The seeker of truth is a mirror for their neighbors. But those who cannot feel the sting of truth are not mirrors to anyone but themselves.

If you find fault in your brother or sister, the fault you see in them is within yourself. Get rid of those faults in yourself, because what bothers you in them bothers you in yourself. An elephant was led to a well to drink. Seeing itself in the water, it shied away. It thought it was shying away from another elephant. It did not realize it was shying away from its own self.

All evil qualities—oppression, hatred, envy, greed, mercilessness, pride—when they are within yourself, they bring no pain. When you see them in another, then you shy away and feel the pain.

We feel no disgust at our own scab and abscess. We will dip our infected hand into our food and lick our fingers without turning in the least bit squeamish. But if we see a tiny abscess or half a scratch on another’s hand, we shy away from that person’s food and have no stomach for it whatsoever. Evil qualities are just like scabs and abscesses; when they are within us they cause no pain, but when we see them even to a small degree in another, then we feel pain and disgust. Within our being all sciences were originally joined as one, so that our spirit displayed all hidden things, like clear water shows everything within it—pebbles, broken shards and the like—and reflects the sky above from its surface like a mirror. This is Soul’s true nature, without treatment or training. But once Soul has mingled with the earth and its earthly elements, this clarity leaves it and is forgotten. So God sends forth the prophets and saints, like a great translucent ocean that accepts all waters, and yet no matter how dark or dirty are the rivers that pour into it, that ocean remains pure.

Then Soul remembers. When it sees its reflection in that unsullied water, it knows for sure that in the beginning it too was pure, and these shadows and colors are mere accidents. A friend of Joseph returned from a far journey.

Joseph asked, “What present have you brought me?” The friend replied, “What is there you do not possess? What could you need?

Since no one exists more handsome than you, I have brought a mirror so that every moment you may gaze in it upon your own face.” What is there that God does not possess? What does He need? Therefore, bring before God a heart, crystal clear, so that He may see His own perfection. “ God looks not at your form, nor at your deeds, but at your heart.” PDF English 450 Pages PDF English 450 Pages PDF English 450 Pages . Excerpts from Introduction of by Arberry: ' The use of the parable in religious teaching has of course a very long history, and Rumi broke no new ground when he decided to lighten the weight of his doctrinal exposition by introducing tales and fables to which he gave an allegorical twist. He was especially indebted, as he freely acknowledges in the course of his poem, to two earlier Persian poets, Sana'i of Ghazna and Farid al-Din 'Attar of Nishapur, Rumi's immediate models.

The first mystics in Islam, or rather those of them who were disposed to propagate Sufi teachings in writing as well as by example, followed the lead set by the preachers. Ibn al-Mubarak, al-Muhasibi and al-Kharraz were competent Traditionalists and therefore sprinkled acts and sayings of the Prophet, and of his immediate disciples, through the pages of their times, furnished the next generation of Sufi writers with supplementary evidence, their own acts and words, to support the rapidly developing doctrine. Meanwhile the allegory, reminiscent of the 'myths' of Plato and the fables of Aesop, established itself as a dramatic alternative method of demonstration.

It seems that here the philosophers were first in the field, notably Avicenna who himself has mystical interests; he would have been preceded by the Christian Hunain ibn Ishaq, translator of Greek philosophical texts, if we may accept as authentic the ascription to him of a version 'made from the Greek' of the romance of Salaman and Absal. Among Avicenna's compositions in this genre was the famous legend of Haiy ibn Yaqzan, afterwards elaborated by the Andalusian Ibn Tufail. Free Download Ccm Bicycle Speedometer Manual Programs For First Time.

Shibab al-Din al-Suhrawardi al-Maqtul, executed for heresy at Aleppo in 1191- only sixteen years before Rumi was born in distant Balkh-combining philosophy with mysticism wrote Sufi allegories in Persian prose, and was apparently the first author to do so; unless indeed we may apply the word allegory to describe the subtle meditations on mystical love composed by Ahmad al-Ghazali, who died in 1126. Such in brief are the antecedents to Rumi's antecedents. When Sana'i began writing religious and mystical poetry in the early years of the twelfth century, he found the Persian language prepared for his task by Hujviri and Ansari. His greatest and most famous work, the Garden of Mystical Truth, completed in 1131 and dedicated to the Ghaznavid rule Bahram Shah, is best understood as an adaptation in verse of the by now traditional prose manual of Sufism. The first mystical epic in Persian, it is divided into ten chapters, each chapter being subdivided into sections with illustrative stories.

It thus gives the superficial impression of a learned treatise in epic is shown by the lengthy exordia devoted to praising Allah, blessing his prophet, and flattering the reigning Sultan. Rumi in his Masnavi quotes or imitates the Garden of Sana'i on no fewer than nine occasions. It should be added that Sana'i, like Rumi after him, composed many odes and lyrics of a mystical character; unlike Rumi, he also wrote a number of shorter mystical epics including one, the Way of Worshipers, which opens as an allegory and only in its concluding passages, far too extended, turns into a panegyric. Farid al-Din 'Attar, whom Rumi met as a boyand whose long life ended in about 1230, improved and expanded greatly on the foundations, laid by Sana'i. Judged solely as a poet he was easily his superior; he also possessed a far more penetrating and creative mind, and few more exciting tasks await the student of Persian literature than the methodical exploration, as yet hardly begun, of his voluminous and highly original writings. His best known poem, paraphrased by Edward FizGerald as The Bird-Parliament, has been summarized by Professor H. Ritter, the leading western authority on 'Attar and a scholar of massive and most varied erudition, as a 'grandiose poetic elaboration of the Risalat al-Tyar of Muhammad or Ahmad Ghazali.

The birds, led by the hoopoe, set out to seek Simurgh, whom they had elected as their king. All but thirty perish on the path on which they have to traverse seven dangerous valleys. The surviving thirty eventually recognize themselves as being the deity (si murgh - Simurgh), and then merge in the divine Simurgh.' It is not difficult to apprehend in this elaborate and beautiful allegory, surely among the greatest works of religious literature, the influence of the animal fables of Ibn al-Muqaffa'. In his Divine Poem, which has been edited by Professor Ritter and of which French and English translations are understood to be in preparation, 'Attar takes as the framework of his allegory a legend which might have been lifted bodily out of the Thousand and One Nights. 'A king asks his six sons what, of all things in the world, they wish for. They wish in turn for the daughter of the fairy king, the art of witchcraft, the magic cup of Djam, the water of life, Solomon's ring, and the elixir.

The royal farther tries to draw them away from their worldly desires and to inspire them with higher aims.' The supporting narratives are, like those of the The Bird-Parliament, told with masterly skill and a great dramatic sense.' The renowned German-born scholar of Rumi, Professor Annemarie Schimmel (1922 - 2003) was also a specialist on Islamic Mysticism, Sufism. Professor Schimmel published 80 books and lectured at various universities including Harvard where she was Professor of Indo-Muslim Culture from 1970-1992.

She was fluent in ten languages including Arabic, Farsi or Persian, Turkish, and Urdu. Annemarie Schimmel's major works on Rumi are: • Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaluddin Rumi. • I Am Wind, You Are Fire: The Life and Work of Rumi. This is Love: Poems of Rumi. • A Two Colored Brocade: The Imagery of Persian Poetry.

• As Through a Veil: Mystical Poetry in Islam. Badi al-Zaman Foruzanfar (1904 - 1970), the highly distinguished Iranian-born scholar of Persian Literature, is universally recognized as the greatest Persian Scholar of Rumi. Forouzanfar's critical edition of Rumi's Divan- e Shams Tabrizi (in 10 volumes) is the best edition available to date. T he most accurate critical edition of Rumi's original Quatrains (Rubaiyat) was also published in 1963 by Foruzanfar. He is also credited with publishing the first critical edition of Rumi's Fihi Ma Fihi which was translated into English by the eminent British-born Orientalist, Professor A. Arberry as Discourses of Rumi. The eminent Iranian-born scholar of Rumi, late Prof.

Abdul Hossein Zarinkoob (1923 - 1999) is widely known and revered among Farsi-speakers for his profound researches and publications on Rumi and his works. Zarinkoob's major works on Rumi are: • Step by Step until Meeting God (about Life, Works, and Teachings of Rumi). • Shams of Tabriz: The Voice-Pipe of Rumi. • Love in Rumi's Masnavi. • Secret of the Reed (Critical and Comparative Analysis of Rumi's Masnavi). • Sea in a Jug (Critical and Comparative Analysis of Rumi's Masnavi). • Persian Sufism: Its Heritage and Spiritual Values.

• Persian Sufi Literature and Its Humanitarian Values and Principles. • A Research on Persian Sufi Mysticism. • A Research on Sufi Mystics in Ancient Iran.

Unfortunately, none of his above mentioned works are yet translated into English ( I've taken the liberty to translate the above titles of Prof. Zarinkoob's works from Farsi into English.).

Coleman Barks' is undoubtedly the most popular and widely read Rumi translation book in America.to his credit, and despite not speaking a word of Farsi or Persian, Prof. Coleman Barks deserves our huge accolades and appreciations for single-handedly introducing and popularizing Maulana Jalaluddin Balkhi 'Rumi' here in America with his truly outstanding and groundbreaking first book on Maulana, which he published back in 1995. It's largely thanks to Coleman Barks that Rumi is a household name and an integral part of American popular culture these days. Barks has since published. Coleman Barks, 21st century poet, likes to point out that Jelaluddin Rumi, 13th century poet, is both the bestselling poet in the United States and the one most often played on Afghan radio stations. Given the current situation, it's unlikely anyone will be able to confirm the latter.

But it is fair to say that one thing currently binding these two warring nations is a poet born in a time when neither country existed. It would be a disappointment if there wasn't a story about how Barks became the country's most popular Rumi translator.

Rumi lore is studded with stories marking beginnings and endings and revelations. Nothing gradual happens to mystics.

Life-changing events are spontaneous and total. Insight flashes; Teresa de Avila falls into an ecstatic trance, a crash, an explosion and everything is different. The story of how Barks, Southern-born poet and University of Georgia English professor, became a Rumi scholar begins in 1977. On the night of May 2, Barks dreamed he was lying in a sleeping bag on the banks of the Tennessee River, near where he grew up. Suddenly a flash of light lit up the sky and, as Barks describes in the introduction to his new book, 'The Soul of Rumi': 'A ball of light rises from Williams Island and comes over to me -- revealing a man sitting cross legged with head bowed and eyes closed, a white shawl over the back of his head. He raises his head and opens his eyes. I love you he says.

'I love you too,' I answer.' One year later Barks found the same figure in waking life: The man was a Sri Lankan Sufi saint named Bawa Muhaiyaddeen who would instruct Barks -- who did not and still does not speak Farsi, the Persian dialect in which Rumi originally wrote -- to pursue his translations. If you are not generally inclined to believe stories about prophetic dreams and other supernatural events, then you are also probably not a Rumi fan. Stories of the mystical and miraculous don't constitute all of Rumi's writings, but they're a part of it.

For better or for worse, they've helped cement his stubborn association with the new age movement. But a suspension of belief, or at least the ability to appreciate the symbolism of a far-fetched story, gives life to Rumi poems. If life, not paper, is the path to the divine, Barks' translations may be closer to Rumi's ambitions than those produced by scholars of Farsi, the Persian dialect in which Rumi originally wrote. Barks deals very little with the original Farsi: He starts by comparing existing English translations, which he then rephrases into his own. Often this means giving up the rhyme and tempo of Rumi's original Farsi, but it allows Barks to bring the poetry a jauntiness and modernity. Rumi's jokes become funnier with Barks behind the wheel.

Thus we get: 'Someone born deaf has no more use for high notes than newborn babies for a fine merlot.' It's a style Barks hinted at when he criticized a contemporary, Farsi-speaking Rumi translator who 'uses words like 'unfathomable' a whole lot.' I've broken through to longing Now, filled with a grief I have Felt before, but never like this. The center leads to love. Soul opens the creation core. Hold on to your particular pain. That too can take you to God.

According to Rumi, not only does our 'particular pain' take us to God, it is God. And in Barks' translations, there's nothing in the world, its worst and best, that isn't holy. Barks explains, 'And if that's true then every kindness and every healing, as well as every disease and cruelty and every terrible sudden screaming is all God. It's all divine.' Art is a place we often go looking for advice when we've run out of other options.

And what's there, inevitably, isn't an answer but a reflection of the suffering we already feel. On this point, Rumi, reduced by grief to simple, unmiraculous reflection, does a pretty good job.

The tomb Looks like a prison, but it's really Release into union. The human seed goes Down into the ground like a bucket into The well where Joseph is. It grows and Comes up full of some unimagined beauty. Your mouth closes here and immediately Opens with a shout of joy there.

'It's a mysterious thing what the soul is,' Barks says. 'No one knows what the soul is. But I think it's the thing that makes symbols, makes stories, it's that overflow part of the human psyche that generates 'War and Peace.' There was no need for 'Twelfth Night,' or 'As You Like It,' it just flowed out of Shakespeare.

Same way with Rumi's poetry; it was all spontaneous. It was part of the work that he was doing with the learning community, he spoke it. Didn't write it down.

He spoke it and then a scribe took it down. And then Rumi would look at the pages and make alterations. But mainly you can say it is jazz, made up at the demands of the moment. It's as spontaneous as a day. And keeps on happening. So certain characteristics of the soul might be that it's generous in its ability to generate things, it's joyous, innately playful and grieving; it's very connected to grief.'

Excerpts from.

Posts

- Bauman Postmodern Ethics Pdf Reader

- Serial Ranczo Sezon 9 Online

- Chameleon 2 Rc4 Install Download

- Keygen Printfil 5

- Spintires Download

- Deadly Innocence Scott Burnside Pdf Converter

- Learn Malayalam Ebook Download

- Quo Vadis 1951 Dublado Download

- Xp Professional Sp3 Serial Number

- Keygen Serial Visualgdb Serial

- El Aprendiz De Brujo Libro Pnl Descargar